Washington/Islamabad, August 25 – Badruddin Haqqani, the key operational commander of the al Qaeda linked Haqqani network, and top Pakistani Taliban commander Mullah Dadullah are believed to have been killed in US drone and air strikes in the tribal region of Pakistan and Afghanistan. Badruddin, the son of Afghan warlord.

Jalaluddin Haqqani, is ranked as a deputy to his elder brother and the network’s chief Sirajuddin and was believed to be killed in one of the five volleys of drone strikes in Pakistan’s Taliban-controlled tribal agency of North Waziristan since August 18.

Four of the missiles hit took place in Shawal Valley, considered to be traditional area of operations of Haqqani network in North Waziristan, and US reports said he may have been killed in the August 21 strike near Miranshah.

The wave of attacks drew strongest protest from Islamabad in recent years when a senior US diplomat was summoned by the Foreign Ministry to lodge their opposition to the attacks.

Badruddin, thought to be in his mid-30s, was a member of the Miranshah Shura Council, one of the Afghan Taliban’s four regional commands, which controls all activities of the militant group in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Senior US officials were quoted by the New York Times as saying that they had strong indications that Badruddin, the key commander of the Haqqani network which is responsible for most of the spectacular assaults on American bases and Afghan cities in recent years, was killed in a drone strike

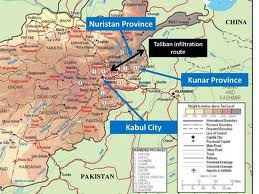

Meanwhile, a statement by coalition forces in Afghanistan said that Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan leader Mullah Dadullah was among 20 militants killed in a “precision airstrike in Shigal wa Sheltan district (of) Kunar province yesterday.” Dadullah, whose real name is Maulana Mohammad Jamaluddin, was made the commander of Taliban in Pakistan’s Bajaur Agency in 2010. He fled to Afghanistan to escape an operation launched by the Pakistan Army. His deputy Shakir too was killed in the airstrike, the statement said.

Badruddin is one of the nine Haqqani family members who have been designated by the US as global terrorists. His brother Sirajuddin is the overall leader of the Miramshah Shura.

Siraj was designated by the State Department as a terrorist in March 2008 and in March 2009, the State Department put out a bounty of USD 5 million for information leading to his capture.

Giving details about the operation, American intelligence officials indicated to the Long War journal yesterday that the remotely piloted Predators and Reapers were targeting an “important Jihadi leader” in the region but his name was not disclosed.

“There are indications that Haqqani has met his demise,” a senior US official said in Washington yesterday.

He said officials were waiting to sift through evidence, including information on jihadist websites, before they could be certain that Haqqani had been killed.

The report said their caution stemmed from previous erroneous claims by American and Pakistani officials about militant deaths in Waziristan, a difficult place to get reliable information. But if confirmed, Haqqani’s death would be a “major benefit to the military coalition in Afghanistan.”

“Badruddin has been at the centre of coalition attacks in Afghanistan as well as mischief in Pakistan,” said the official. The Haqqani network has been blamed for some of the most spectacular assaults on US bases and Afghan cities in recent years.

By Friday evening, reports of Badruddin Haqqani’s death were circulating in Pakistan’s tribal belt.

In Washington, the White House and the CIA, which carries out drone strikes in Pakistan, declined to comment.

The latest string of drone attacks, most of them carried out in Shawal area of North Waziristan Agency, has renewed tensions between Pakistan and the US.

Nearly 40 suspected militants have been killed in these attacks, including a Kashmiri jihadi named “Engineer” Ahsan Aziz. Former Jamaat-e-Islami chief Qazi Hussain Ahmed recently led funeral prayers in Mirpur for Aziz, who was killed in a drone strike on August 18.

Badruddin Haqqani runs the Haqqani network’s day-to-day militant operations, handles high-profile kidnappings and manages its lucrative smuggling operations, according to a report by the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point.

In August last year, Afghan intelligence released intercepts of Badruddin Haqqani directing a daring assault on Kabul?s Intercontinental Hotel. Three years before that, he held a reporter for The New York Times, David Rohde, hostage.

The last major successful drone strike in Pakistan was the killing of al-Qaeda deputy leader Abu Yahya al-Libi in June.

US drones yesterday fired six missiles at three locations in Shawal Valley, destroying mud-walled compounds and two vehicles, Pakistani security officials and a Taliban commander said.

Among the 18 people killed was Emeti Yakuf, a senior leader of the East Turkestan Islamic Movement, a group from western China whose members are Chinese Uighur Muslim militants.