Nafisa Hoodbhoy, the first female reporter in Pakistan, talks about the country’s ties with China, civil-military relations, terrorism and much more.

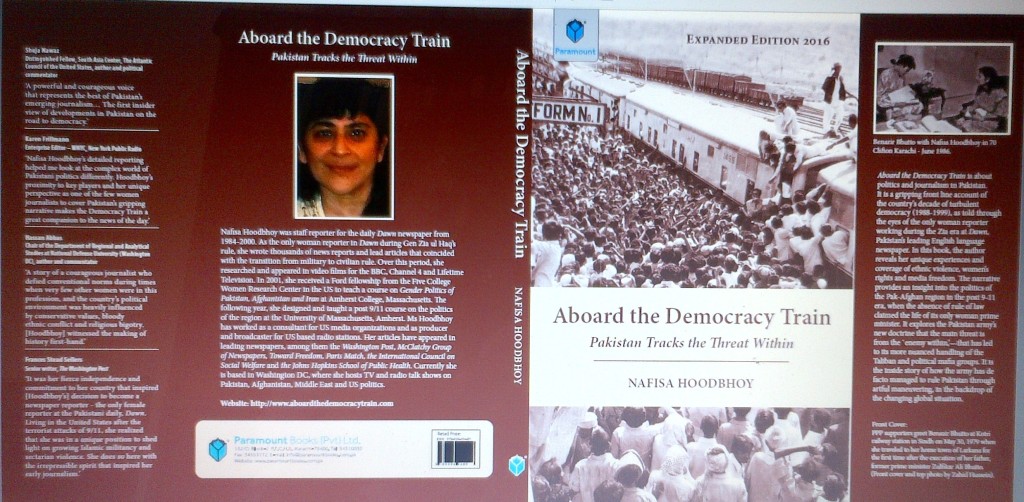

Nafisa Hoodbhoy is a senior Pakistani journalist and author based in the US. She recently authored Aboard the Democracy Train: Pakistan Tracks the Threat Within, a book about politics and journalism in Pakistan. As the only female reporter working for Dawn during Gen Zia ul Haq’s rule, she wrote news reports and articles that coincided with the transition from military to civilian rule.

What do you mean by Aboard the Democracy Train?

Well, I thought that this would be a captivating title because of the fact that when I came back (to Pakistan in 1984), [I] was appointed given the fact that I was the only women reporter. So, my editor asked me to accompany Benazir Bhutto when she made a bid to become Pakistan’s first and only female prime minister. That is why I travelled with her on the train.

When we passed through different cities and towns in the interior Sindh, I thought that the people were deprived of food, clothing and shelter. And the way they responded to Benazir Bhutto gave me the idea that Pakistan was waiting for true and representative democracy. Later on, that idea or image was so powerful in my mind because, of course, the history of Pakistan has been the history of deprivation of the rights of people.

Consequently, I made it the cover of my book.

What is the prime objective of your book?

I think that I have had a great opportunity not only as a reporter in Pakistan, but also having gone to the United States and doing radio programmes from there after 9/11. I have been able to see how the United States interacts with Pakistan; Pakistan’s foreign policy plays a huge role in the way that the transformation has occurred in the last few years.

Being given this unique opportunity to observe things at a very close level, I thought that I should share my experiences and observations, and turn them into readable accounts which is what inspired me to write this book.

In your book, you write that in Pakistan “the military establishment has infiltrated ethnic, religious and political parties to bend the situation in their favor”. Could you please explain this?

Anybody who has lived through the history of Pakistan will tell you that we have never had a functioning democracy in this country. As a reporter who covered elections regularly, I had the opportunity not only to be closed to politicians, but also to observe how elections were rigged. It is not something that one arrives in one day; it is rather through consistent reporting and observation I was, for example, able to see that how the Muttahida Quami Movment (MQM) was created.

In those days, MQM was infiltrated by the military which wanted to see the Mahajirs (refugees) channel there in such a way that it could be used by the military to prevent the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) from grabbing the power at the Centre.

I was witness in those days that not only the military, but also Nawaz Sharif, as he was a businessman and chosen by the military. In many cases, the combined opposition to former Benazir Bhutto was headed by Nawaz Sharif, too. That is why I got a very close look the way the military manipulated ethnic, religious and political parties in order to prevent people’s rule in the country.

In your estimate, what are the motives behind military coups in Pakistan?

It is an extremely complex situation but the fact is that the politicians are unable to deliver. And why are politicians unable to deliver? In my opinion, one of the reasons behind is this that the military does not allow freedom for institutions to develop. For example, in Pakistan, the judiciary has been curbed; the media has been curbed. These are cornerstones of any functioning democracy.

The present reform system has been controlled. However, we need to have a better education system; we need to allow institutions to grow. So, when this does not happen, and the politicians who are ruling the country during the same time, they fail. Because there is not enough planning at all levels. In this context, when politicians fail, the military takes over the control by saying that the political establishment is unable to bring about democracy in the country.

What has been the US’s role in undermining democracy in Pakistan?

I have to explain this one thing, which is that the United States does not go around trying to destabilise the nations around the world. What it does is it follows its own national interests because countries do not have emotions. They neither have friends nor enemies. In fact, they have only interests. For example, America’s interest was to get Pakistan as an ally in order to crush the Taliban and other militant forces, like al-Qaeda there. They did so to ensure that the people like Osama Bin Ladin never find sanctuaries.

It is not right to say that America is out to sabotage democracy around the world. However, it is too easy for us to say that America is against democracy and looks only for its own interests. As for interests, there is no doubt that every nation looks for its own interests. But the only difference they have the power and we do not have the power.

On the other hand, I would say that the foreign interventions in these regions are also important. Ever since the 9/11, America intervened. It opened a Pandora’s box in this country. Two things went out of control because of Pakistan’s history of shielding the Taliban. The fact is that if Pakistan wanted to get US aid and, of course, Pakistan does want to continue the US assistance. That is why it had to say yes to the United States. But implicitly it went against a policy of no interference in Afghanistan, which complicated things and brought terrorism to a boiling point in this country.

When the US interferes, there is often no understanding of how this can open up sectarian class and all types of differences which exist in lawless society like Pakistan.

What challenges did you face as the first female reporter during General Zia-ul-Haq’s regime?

I came at a time when women had actually disappeared from public view and the concept of chadar aur chardivari (the veil and the four walls) was very strong. Women who had protested against laws of evidence had been tear-gassed in 1981. So, I came only a few years later.

Interestingly, when I would go to public functions, the male reporters would start looking at me as though I was doing something wrong. Also, when I would go to events, I would even be asked whether I would be feeling strange because I was the first female reporter in Pakistan’s traditionally patriarchal society.

Besides myself working as a journalist, it was interesting that in 1981 Women Action Forum was formed and it was actually formed as a reaction to General Zia-ul-Haq’s rule, because he had enacted laws against women, including the Hudood ordinance, laws of evidence, etc. These laws were enacted in order to push the women back to their homes.

How did Pakistan transform politically and religiously under Zia?

It was [a] very, very transformational period for Pakistan. The major reason was the guns were coming in for the Afghan war. Karachi, the former capital of Pakistan, was transformed into the centre – guns would be sent from there to Peshawar for Mujahideen to fight the Soviets in Afghanistan.

Zia had also banned the political parties. Consequently, the people were splitting up into ethnic groups. One of its examples is the MQM, which rose during Zia’s time. On the other hand, the religious parties also started gaining power. This is what happens when you do not have democracy.

In a nutshell, there were no ideological parties. Following Zia, there were also not ideological parties and democracy in true sense, including Benazir Bhutto’s PPP.

However, the religious and political transformation during Zia’s time was very deep, as well as it went on at every level in the society.

How do you view the current civil-military relations in Pakistan?

In the last 70 years, so much has happened in Pakistan. I think now the military has started to recognise that the people are fed up of martial laws. So there is no longer the acceptance of military rule, because we have already had two long military rules by General Zia and General Parvez Musharraf.

Even if former President Asif Ali Zardari was not a competent ruler, the military allowed him to continue his rule because they realised there was no appetite of democracy for dictatorship. But I would say that when elections were held in 2013, there was an understanding by military that it could not be business as usual.

As I write in the last chapter of my book, the way this present government came in, then Nawaz Sharif and Imran Khan came in a very curious way in the sense that the establishment used the Taliban to attack the parties which were secular, including: ANP, MQM and PPP. Therefore, the two parties Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (PTI) and Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) were facilitated by them.

I think Imran Khan rode the wave because he understood that the Taliban were a big force at the time. He showed closeness to the Taliban, while the army decided to use him. So he was allowed to gain power by stopping them from attacking his rallies, etc.

In a very devious way, Imran Khan and Nawaz, both of them, I would say, are parties of the establishment, which were ushered by the Taliban.

Even now there are many, many games being played. It is not like establishment or military’s sympathies toward any groups. Its primary goal is to control them or use political parties.

In Pakistan, politicians are nothing. In fact, they are people to be dispensed with. Remember, political parties are a creation of the establishment. For example, we do not have a defence minister in the country right now because the army makes all the decisions. There is no pretense of having a political figure or defence secretary or defence minister because there is no need for all that stuff. Everybody knows that the army makes all the decisions.

It is not just foreign affairs; the army is now making decisions in every, every aspect of life.

Why is ideological politics non-existent in Pakistan?

Because the political space has not been provided to them, and it should be provided to political parties to groom and train younger people. If there is no history of democracy, what is the role model? What can you look to the past, if all the politicians are mere creations of the establishment? Then, there is not much scope for grooming political parties, is there?

Following the attack on the Army Public School, what change do you perceive in Pakistan’s internal and external policies?

In 2014, the operation Zarb-i-Azb was launched. Already, the military had started clamping down, and before that the Karachi operation was launched. But the APC was another big jolt for them, and the people with whom the army had had contacts, in the past, like Fazlullah. It is my belief that they let Fazlullah escape from Swat by letting him go to Afghanistan. In fact, there is quite evidence on that discourse.

When those people returned to kill innocent children, it shook things up in this country. As a result, the army did react very promptly by intensifying Zarb-i-Azb. After that, there is specific targeting of militant[s] across the country, where they knew they were hiding in Federally Administered Tribal Areas and Kyber Pakhtunkhwa.

In a nutshell, it renewed the anger in the army that these people are still present despite frequent bombardments in the aforementioned areas.

Following the attack, the army has been able to raise its head little bit. The reason is: Pakistan had been consumed by terrorism prior to that. Therefore, they managed to clean up quite a bit Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, where there used to be routine bomb attacks in the past. For example, before 2014, there were usual bomb attacks there.

As for Balochistan, hundreds of Hazaras would be slaughtered at one time. Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ), which is active in Mastung, Balochistan, they were chased out. Malik Ishaque, the head of LeJ, was killed in an encounter. Besides him, some of his finances were killed.

After these all, the military used intelligence; it tracked all the political and sectarian groups that had been committing terrorist acts. In this regard, Altaf Hussian himself was tracked. Also, for the first time, the army said a very interesting thing that MQM is basically a terrorist organisation with a political mandate instead of the other way around. It redefined MQM. So, having treated it as terrorist then, of course, what follows after that. And it is continued to follow after that.

Yes. There have been major changes in internal policies.

Externally, what they did: it raised Pakistan’s profile in the outside world. I think that Pakistan army’s capability has been recognised in the outside world. It has allowed Pakistan’s status in that sense to be lifted a little bit higher that it was able to control terrorism.

Of course, terrorism has not ended now, and we do not know what the future of terrorism is in the country. Certainly, I believe that not unless you bring sweeping changes, giving the people the right to understand that what the hell is going on inside the country. Just, blindly accepting military rule is not a cure. And military courts can never be a substitute for the rule of law; the way the state narrative continues can never be a substitute for real debate and understanding for critical analysis, for which we really need to project what is going on and understand things better. So, I think that is the way our country is headed right now.

Is Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif creating a space for the military establishment?

I think that he has a better understanding of the military establishment than the other parties or chairpersons. In history, he came at a time when the military was much more in a position to recognize that unless it combated the enemy within, nothing could be done.

In 2013, it was a turning point for Pakistan, and the military recognised that the businessman who they turned into a politician was perhaps the only one who could have the smartness to work with them in such a way that he keeps his mouth shut, he often does not speak the truth when he goes out of the country. So, they need a man like that because they do not need a man who is rabble-rouser, and who gathers crowd. They need someone who can toe the line, and I think he is delivering very well for that.

How has militancy strained Pakistan’s ties with its neighboring countries?

This is true that even at a time in Pakistan’s history when it has succeeded fighting militancy. It’s past history with its neighbours, and I will not go beyond 2011, has made it extremely unpopular. Today, we are at a very low point in our relationship with our neighbours. For example, Afghanistan is blaming us for supporting the Afghan Taliban and the Haqqani Network in order to destabilise the Afghan government. India is convinced that we are still sheltering Kashmiri separatists, and militant groups, like JuD [Jamaat-ud-Dawa] which openly has processions and shuts down roads and markets. In this context, the people like Hafiz Saeed, etc, are roaming free. That is why they are very vocal about Pakistan’s support toward terrorism.

As far as China is concerned, she is looking the other way because she needs Pakistan for its economic interests.

Between Iran and Pakistan, on the other hand, are also problems due to Sunni elements who use Balochistan border to inflict attacks on Iran. Anyway, that is a separate issue.

On the other hand, Pakistan is close to Saudi Arabia also makes more tense the relations with Iran.

What about the US?

With the United States, I would say that relationship is still uneasy one. Right now, the US itself is in a state of transition due to elections. And the Congress has a lot of people who say that Pakistan should be cut off, so much so, sometimes they are very loud by saying that 15 years on Pakistan refuses to stop supporting the Haqqani network.

Worryingly, Mullah Akhtar Mansour was killed in a drone attack in Balochistan. In fact, Balochistan still continues to be the hub of Quetta Shura. Therefore, these things are making Pakistan’s relations unpopular with America and rest of the world.

Is China still complainant about Uighurs’ safe sanctuaries on Pakistan’s soil?

To my knowledge and understanding, Pakistan has done a wonderful job to rid of foreign militants, like Uzbeks, Tajiks, Chechens and Uighurs. It’s Taliban that creates problem.

With Uighurs, in recent times, there are no complaints from China.

Does Pakistan still differentiate between the good and bad Taliban?

Well, Pakistan keeps saying, especially from 2014, that it does not differentiate any more between the good and bad Taliban. But if you talk to senior government officials inside Afghanistan, they will say that Pakistan still differentiates between good and bad Taliban.

The only thing which I think has happened is that the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan has gone to Afghanistan and many of its leaders, who are disillusioned with Pakistan, are now joining the Islamic State. That is why Afghanistan is accusing Pakistan of supporting IS inside Afghanistan.

We know for the fact that the great game is going on and Pakistan does need a strategy for pursuing its policies of strategic depth inside Afghanistan. So, as long as that happens, it will continue to differentiate between the good and bad Taliban.

What are your thoughts on the Gwadar port project and security situation in Balochistan?

If the Gwadar port project is going to be a project of the federal government without input from the Balochistan government, then it is headed for a major showdown. In this context, the questions arise: How can you come as a foreign invader in your own country? How can you support the interests of a foreign country in your own country and support your own military restrict without recognising that this is in a province where people have suffered from generations of neglect? So, if they are committing this blunder, then they will have to pay for it because this is an opportunity for Pakistan to enhance itself in order to enrich itself by bringing people to mainstream, educational opportunities.

I still think that the control over the Gwadar port project is so strong that even the officials of Gwadar recognise that their jobs are very precarious that if they detract from the policies of the federal government, then they can lose their jobs.

However, it is very significant now for the democratic forces in Balochistan in particular and in Pakistan in general to demand that to be given a say in the Gawadar port. Otherwise, this is also going out of their hands.

The federal government and the military have provided something like 10,000 security personnel to secure Chinese nationals, who will be coming in. And they are treating the Baloch as a problem, instead of taking them along with themselves.

As long as they continue to treat them as a problem rather than the people of the soil, the security situation will never improve. However, the people are people, and they feel affronted by these people coming in and behaving like foreign powers by simply enriching themselves only.

So, that is my prognosis that until people, intellectuals, different people who have a vested interest in seeing the economic situation improve and the participation of the people, I think they really need to speak out and write to have an impact. If you do not speak up, then you are dead meat.

Is CPEC [China–Pakistan Economic Corridor] really a game changer for Pakistan in general and Balochistan in particular?

Supposedly, China is now really rushing and their officials are coming to Islamabad. In a nutshell, they are very anxious to build this project because China is an emerging power. But politics inside Pakistan keeps postponing, which prevents things from happening. However, in my estimate, Chinese are pushing for greater economic transformation. The reason is: they have their own interest. But politics in Pakistan is getting in the way.

As for the question, it can be a game changer but it depends on how it is approached.

The government of Pakistan has lots of work on its hands. It really needs to get its house in order, and yes of course promote industry and also promote power by allowing your good to start competing. Once Chinese goods reach Pakistan and they are sold at cheaper rate than Pakistani goods. Then, I can see the problems growing for Pakistan.

Once non-Baloch are inducted into Gwadar port, and they start working in Gwadar. Then, I can also see problems growing for the local people.

So, there is a need to make provisions to plan, plan, and plan. Unless you do that it cannot be a game changer.

How much is Pakistan benefiting from its all-weather friend China?

China is now quite involved in Pakistan; as much as I know, it is giving much more assistance than America to Pakistan. China, on the other hand, is in Pakistan’s neighborhood, and it unlike America leaving Pakistan. Remember, if America is eight thousand miles away and can get involved in Pakistan primarily due to Afghanistan. So, why not China?

China has quite invested in Pakistan’s infrastructure, which is a good thing. And I do think that China tends to support Pakistan at international levels and issues. So, many things for which there are objections, for example, India is getting into the nuclear club and if Pakistan wishes to do the same it has few friends other than China that will support it at a UN level. For that, I think China is a very good partner for Pakistan at the international level.

On the other hand, they are willing to negotiate in Afghanistan, and that is a plus for Pakistan. As a neutral country, they are willing to sit and negotiate a deal between the Taliban and the Afghan government.

Liked the story? We’re a non-profit. Make a donation and help pay for our journalism.