Pakistan’s catastrophic monsoon floods of 2010 – which scientists link to climate change and global warming and which has mostly hurt the farmers who eke a living along the Indus River – have turned into a defining moment for the nation.

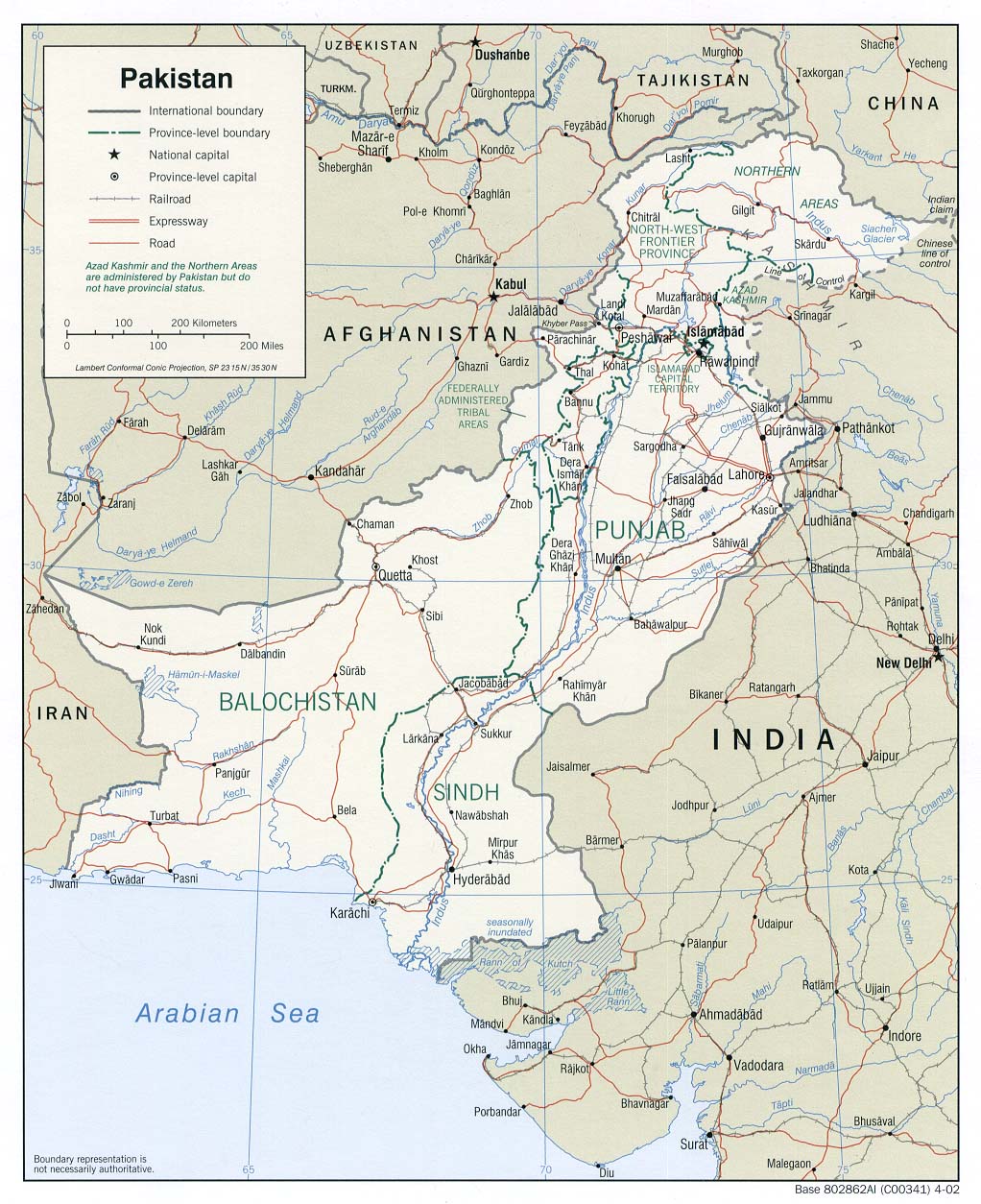

The world watched with disbelief as the torrential rains, which bloated the Kabul and Indus rivers, swept away hundreds of people, homes and livestock in the north of Pakistan. As bridges and hotels collapsed in the scenic Kalam and Swat valley, the northern areas of Gilgit and Baltistan were cut off from the world.

Despite this, crisis-ridden Islamabad appeared unaware and unprepared for the most devastating natural disaster in its history.

Only then – as the Indus River, swollen to nearly 12 times its normal size, wreaked havoc on villages and towns in its southward journey to the Arabian ocean – did the government wake to the existential threat to Pakistan.

“It’s like partition,” said a dazed PPP Prime Minister Yusuf Raza Gilani, who compared the sheer scale of the devastation caused by the 2010 floods to the events of 1947, when Pakistan was carved out of India.

Prime Minister Gilani, who has stepped into the late Benazir Bhutto’s shoes, had the unenviable position of answering to millions of people who voted for the PPP because of its founder Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and his daughter, Benazir’s pledge to provide “Food, Clothing and Shelter” to the people.

The government came under global scrutiny as the media zeroed in on shirtless villagers stranded on highways, hands outstretched with vessels for food and drinking water. Modestly draped mothers, clutching their infants, waded through waistdeep currents, farmers sloshed through the waters with sheep on their backs and people waited for rescue helicopters on islands along river beds that looked like chapattis (an Indian flatbread) floating in gravy.

Adding insult to injury, Pakistan’s President Asif Ali Zardari chose the occasion to visit his family’s chateau in France. His meeting with President Nicholas Sarkozy was ill-timed, given that French prosecutors prepared a case against Sarkozy for funding his political campaign through kickbacks from the submarines provided to Pakistan. Zardari is also named for receiving kickbacks, although he was in prison when the French engineers building the submarines were killed in 2002.

But in July 2002, President Zardari was en route to London to coronate his eldest son, Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, as the party co-chairman. It was a program arranged ahead of time. As hundreds were swept away by the deluge and their sufferings appeared in the world media, his ill-timed foreign tour would send a message of disconnectedness with the people.

The US quickly demonstrated the importance it attached to Pakistan, becoming the first nation to respond with USD 50 million aid, helicopters, boats and halal meals. Helicopters were sent to the Gilgit Baltistan area to rescue stranded people. As torrential rains rushed down the denuded Koh-i-Suleman mountain range, the US coordinated with Pakistan’s federal National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) and the army to save villagers fl eeing the rising Indus waters in southern Punjab and Balochistan.

Early into the disaster, US Secretary Hillary Clinton took to the airwaves in Washington DC to appeal to the American public to come forward and donate to the flood victims. It was a commendable move, laced only with the irony of being issued while President Zardari fiddled in London.

The UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon’s visit to flood-ravaged Pakistan and his declaration that he had before never seen such devastation gave pause to those who were listening. As the UN declared that the disaster was bigger than the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, the 2010 Haitian earthquake and Pakistan’s 2005 earthquake combined, the world reached deeper into its pockets in a gesture on a scale that seemed like it might just fulfill the humanitarian needs of the flood’s victims.

But as weeks went by and the world media depicted poor, ill fed and homeless people displaced by floods, it did nothing to win global confidence. The UN’s first fund appeal for USD 460 million fetched 70 percent of its target with great difficulty. That forced the UN to launch a second appeal for USD 2 billion. Still, as winter set in, UN officials, working hard for flood victims in Pakistan, reported that they had already run out of essential supplies.

In his visits to Washington, Foreign Minister Shah Mahmood Qureishi told the world that if it did not help Pakistan in the flood relief efforts, the nation would fall prey to militants. It was an argument repeated like a mantra. Indeed, where the PPP government had fallen short of providing for the enormous needs of flood ravaged Pakistan, Islamic fronts for jihadist organizations had emerged to dispense relief aid.

If the world needed proof that floods had not washed away the militants, they did not have to wait long. Barely had the floodwaters stopped ravaging communities in the north of Pakistan and the Punjab than the suicide bombers began detonating. A succession of suicide blasts on religious processions in Lahore, Quetta and against security officials in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa would convince the world that the bombers were alive and ticking.

As the Indus River made its south ward journey toward the riverine areas of Sindh – wiped clean of the marshy jungles cut down at the height of the dacoit menace in 1992 – it threatened the thickly-populated towns of upper Sindh. The PPP government issued flood warnings in its home turf – Sukkur, Shikarpur, Jacobabad, Shahdadkot, Dadu, Badin and the southern town of Thatta – forcing millions to evacuate their homes.

Still despite trains and bus services run by the government for the flood affected to go to Karachi, the victims preferred to take temporary shelter with relatives or simply move to higher ground. Indeed, with floods coinciding with the ethnic flare-up between Pashtuns and Mohajirs in Karachi, the rural Sindhis, already battered and robbed of their life savings, took chances with the vagaries of nature rather than a tense ethnic situation in the city.

There was high drama in Bhutto’s birthplace of Larkana, where the government worked frantically to make cuts in Kirthar canal to save the graves of Zulfi kar Ali Bhutto and his children – Benazir, Murtaza and Shahnawaz. PPP officials rushed to create a four-kilometer-long embankment around Garhi Khuda Baksh in Larkana to save the graves of the Bhuttos, whose murders have come to symbolize the eternal sufferings of the people of Pakistan.

Sindh and southern Punjab swirls with tales of feudal lords, including those from the ruling party, who arm-twisted irrigation officials to breach the dikes and save their lands. A pattern emerged where the most influential managed to protect their assets at the cost of the weakest. It would increase resentment in an environment where millions lost their crops and livestock and became internally displaced persons in their own territory.

In October 2010, a survey conducted by the World Bank and Asian Development Bank said that Pakistan’s floods caused an estimated USD 9.7 billion damages to homes, roads, farms and personal property. PPP officials called the figures grossly under-estimated. There were fears that in an agriculturally based economy like Pakistan the damage to the crops alone could be as high as USD 43 billion – 25 per cent of its Gross Domestic Product the year before.

About two thousand were killed in Pakistan’s floods – dramatically lower than the estimated eighty thousand casualties caused by the earthquake five years before. Still there was more bad news ahead, as hundreds of thousands fell victim to acute diarrhea, respiratory infections, skin disease and malaria. Children who saw their parents being washed away had been traumatized and put up for adoption.

Under world scrutiny, Pakistan made payments of PKR 20,000 (USD 233) in four installments to each family. The United Nations and civil society networks injected a modicum of transparency that involved disbursing aid after verifying the national identity cards of flood victims. Still, double payments occurred, as did complaints from families that they had received no money. With food supplies running out, the UN was faced with the difficult choice staggering the aid or giving people less than their nutritional requirements.

For the US government, the biggest concern is that the economic devastation created by the floods will fuel militancy. The army operation against the Taliban in Swat, for example, resulted in massive losses of infrastructure and livelihood for 2.9 million residents of Malakand division. Barely had government surveys reported that the division would need USD 1 billion for recovery, when the floods struck.

Awami National Party’s Minister for Information, Mian Iftikhar Hussain touched a note with the people when he declared, “First we were devastated by the terrorists. Whatever was left was finished by the floods.” For the ANP minister, it was a particularly emotional time, when, just prior to the floods, the Taliban had killed his only son.

The US would prioritize its aid programs to Pakistan with a view to thwarting potential militant attacks. In September 2010, the Obama administration diverted USD 831 million set aside under the Kerry Lugar Berman act for Pakistan’s developmental needs like energy and water and earmarked it instead for humanitarian assistance in FATA and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

But with the US and Europe waging their own financial battles for recovery, the US Coordinator for Economic and Development Assistance, Robin Raphael urged Pakistan to pass meaningful reforms, including expanding its tax base. There was a muted response from the government. The feudal ruling elite has traditionally shunned land reforms, even as the urban industrial class is hostile to suggestions that it should pay more taxes. There was consensus to raise sales tax, which would have the consequence of raising prices for already stressed consumers.

The fact that the floods struck in the post-9/11 scenario and not when the world was busy somewhere else should give pause to Pakistan’s observers. With aid coming in, the civilian government has gone into autopilot – leaving flood recovery and civilian development to foreign and international organizations. As people watch to see if the leadership cuts back on their extravagant lifestyles, the international community, too, has put Pakistan under a microscope to see if it is able to get its act together.