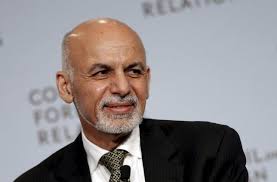

(Credit: inreuters.com)

After his swearing-in in September 2014, President Ashraf Ghani of Afghanistan approached Pakistan sensibly. He did not demand military operations against the Haqqani Network and other Taliban networks based in Pakistan because he knew Islamabad would never do that. Rather, he pleaded with Pakistan to bring the Taliban to the negotiating table. Despite trying to smooth over relations with Pakistan after taking over the country from his predecessor, Hamid Karzai, Ghani’s stance was clear. He repeatedly said that Pakistan is in a “state of hostility with Afghanistan” and uses its proxies–chief among them, the Taliban–to exert pressure on Afghanistan for strategic gains.

This strategy of pursuing peace talks did not yield the desired result for Afghanistan. There were some occasional talks over the last two years, but the fighting has never quite gone away. The Taliban have once again vowed to launch a series of brutal attacks all over Afghanistan, invalidating and disregarding Ghani’s pleas for peace talks. A suicide attack and gun battle in Kabul in front of an National Directorate of Security (NDS) office claimed 64 lives and left 347 wounded on April 19, for example.

The Taliban has done this very thing throughout the past 13 years. They give glimpses of hope for peace in the winter months, since they cannot fight in the cold, only to take up arms again once their traditional fighting season begins.

Following the Kabul attack, Ghani summoned a joint session of the two houses of parliament. He addressed the nation and made bold announcements unlike any leader since Mohammad Najuibullah in the 1990s. Ghani said he no longer wants Pakistan to bring the Taliban to the negotiating table. He also added that the Taliban shed the blood of their own people and land for others’ interests. He added that the period of amnesty and soft behavior was over. Taliban who have been sentenced to death shall be executed soon, Ghani pledged. Despite these bold remarks, he said that Afghanistan’s door is open to those who lay down their weapons and put an end to militancy. His stance was applauded by many Afghans on social media. People of Helmand province subsequently held a rally in support of the president’s remarks.

This is a major shift in Afghanistan’s outreach strategy to Pakistan and the Taliban. Karzai played at soft diplomacy with Pakistan throughout his presidency, in a bid to convince Islamabad to bring the Taliban to peace talks. He once publicly stated that he would side with Pakistan if there were to be a war between the United States and Pakistan; he even called the Taliban his “brothers.” But none of this rhetoric produced results.

Ghani’s statement at the joint session was not driven merely by emotion. He laid the ground for his strategy. Pakistan has always disowned the Taliban, but Ghani’s multilateral diplomacy essentially saw Pakistan confess that the Taliban are trained and sheltered in Pakistan. During his tour to the United States in March, Pakistan’s foreign affairs adviser, Sartaj Aziz, admitted that Pakistan houses the Afghan Taliban.

On top of everything, Ghani is making advancements on diplomatic and military grounds with regional countries. His approach toward Central Asian countries is another example of his pragmatic diplomacy. Central Asian countries share the same fear of Islamist expansion in the region, as does Russia. Ghani’s national security adviser and top decision maker, Hanif Atmar, played a considerable role in furthering diplomatic missions with Russia, China, and India. Atmar traveled to India in November 2015 and China in April 2016. His visits with Russian officials and tour to China brought fruit militarily. China offered military aid to the Afghan National Army following Atmar’s visit to Beijing.

Moreover, after Russia allegedly approached the Taliban to help the group fight ISIS in Afghanistan, Atmar tried to convince Moscow that it was in its best interest to support Afghan forces instead of the Taliban–not only to fight ISIS, but all militant groups. Following his talks with Russian officials, Moscow gifted 10,000 automatic rifles to the Afghan Security Forces. Ten thousand automatic rifles might not mean a lot for a country’s military, but Moscow’s willingness for military cooperation speaks to the success of Ghani’s regional outreach.

The Taliban’s number one demand for a long time has been the withdrawal of the U.S. military from Afghanistan, but they continue their offensives, even after the U.S. military completely ended its combat mission in 2014. Thirteen years of appeasement and amnesty could not convince the Taliban to cut a peace deal. It is now sensible to stop investing Afghanistan’s resources in peace talks and start investing them in building up the country’s security forces. Finally, Afghanistan must put more diplomatic pressure on Pakistan and encourage the international community to do the same. This is now Ashraf Ghani’s plan.

Samim Arif is an Afghan Fulbright scholar. He studies Political Journalism and Public Relations at Indiana University.