ISLAMABAD: Chief of Army Staff (COAS) General Qamar Javed Bajwa said on Sunday that democracy in the country was fostering with time.

The army chief was speaking to the media at Arif Alvi’s oath-taking ceremony. “Democratic institutions are quickly becoming more robust and will only get stronger with the passage of time,” Gen Qamar was quoted as saying. “This is an important day for the continuity of democracy in the country,” the COAS added.

Alvi was sworn in as Pakistan’s 13th head of state in a ceremony held at Aiwan-e-Sadr in Islamabad. Chief Justice of Pakistan Mian Saqib Nisar administered the oath in a ceremony that was attended by top civil-military brass including Prime Minister Imran Khan, Bajwa and Chairman Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee Gen Zubair Hayat. Saudi, Chinese diplomats also attended the presidential oath.

The newly-sworn in president was later given his first guard of honour by the smartly turned out contingents of the armed forces at Aiwan-e-Sadr.

Alvi is succeeding Mamnoon Hussain, who took oath as 12th head of state on September 9, 2013 after his election as a candidate of the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N).

It is pertinent to mention that civil-military relations have always been subject to controversies in Pakistan. The relations went particularly sour during the tenure of the erstwhile ruling party Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N), following the controversial Dawn leaks.

After the eviction of former PM Nawaz Sharif by Supreme Court in the infamous panama leaks case, the PML-N leadership, especially Nawaf Sharif, openly criticized the role of Pakistan Army and even accused it of cross-border terrorism in an interview.

In the past, Pakistan has been viewed in the west as a country influenced by its armed forces, but the country has witnessed positive chances in this narrative since the arrival of the Pakistan-Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) government, led by Imran Khan.

Soon after taking charge, PM Imran Khan went to GHQ where he held an eight-hour long with the military heads. The PM was briefed on the overall security situation of the country as well as on the workings of the army.

On September 6, during a ceremony held in the honour of the martyrs of Pakistan Army, PM Imran Khan reiterated that the government and army was on the same page, which is to help Pakistan stand on its own feet. He went on rebuff all rumours regarding a possible rift between the government and army, and said that Pakistan Army, like other institutions, was working in close coordination with the government.

US Pakistan talks prompt vow to reset ties after prolonged spat – By Asad Hashim Al Jazeera (Sept 5, 2018)

Pompeo has held talks with Pakistan’s prime minister and foreign minister, as the two erstwhile strategic allies seek to mend ties that Pakistan has said have become “almost non-existent” in recent months.

Pompeo met Prime Minister Imran Khan and Foreign Minister Shah Mehmood Qureshi in the Pakistani capital Islamabad on Wednesday, in a set of talks both sides described as a “positive beginning” to rebuilding the relationship.

Army chief Qamar Javed Bajwa, whose institution has ruled Pakistan for roughly half its history and still controls aspects of security and foreign policy, was also part of the talks.

“We have still got a long way to go, lots more discussion to be had,” Pompeo told reporters before leaving Islamabad for his next stop, the Indian capital New Delhi.

Qureshi will meet Pompeo again in Washington DC later this month, following his attendance of the UN General Assembly. He will also be travelling to Kabul shortly for talks with Afghan authorities, he said.

‘Alignment and convergence’

The talks on Wednesday focused on opportunities to reset the relationship and for greater cooperation on the war in Afghanistan, particularly on Pakistan’s role in the political reconciliation process with the Taliban, Pakistan’s foreign minister told reporters.

“The US has been evaluating its policy, and they have reached the conclusion that the solution in Afghanistan is a negotiated political settlement,” said Qureshi. “And here once again you will see an alignment and convergence between the US and Pakistan.”

Pakistan and the US have differed greatly over the conflict in Afghanistan, with the United States and Afghanistan often accusing Pakistan of offering sanctuary to leaders of the Afghan Taliban and its ally, the Haqqani Network.

Pakistan denies the charges, saying it has acted indiscriminately against all armed groups on its soil, and in turn accuses Kabul of allowing elements in the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP, also known as the Pakistani Taliban) to operate in that country’s eastern provinces.

Pompeo said the talks on Wednesday focused on deliverable outcomes.

“We made it clear to them – and they agreed – that it’s time for us to begin to deliver on our joint commitments,” he said. “We have had lots of times where we have talked and made agreements, but we have not been able to actually execute those.”

“And so, there was a broad agreement between myself and Foreign Minister Qureshi, as well as with the prime minister, that we need to begin to do things that will actually begin to deliver, on the ground, outcomes so that we can begin to build confidence and trust between the two countries.”

State Department spokesperson Heather Nauert, meanwhile, said Pompeo commented on Pakistan’s role in neighbouring Afghanistan and the wider region during the talks.

“In all of his meetings, Secretary Pompeo emphasised the important role Pakistan could play in bringing about a negotiated peace in Afghanistan, and conveyed the need for Pakistan to take sustained and decisive measures against terrorists and militants threatening regional peace and stability,” Nauert said.

Funding slashed

The US-Pakistan relationship has remained troubled since President Donald Trump assumed power last year.

In January, Trump cut more than $1.1 billion in security assistance to Pakistan, accusing the country of “lies and deceit” in its role in the Afghan conflict.

On Sunday, the US confirmed that $300 million in a Coalition Support Funds reimbursement, which was initially suspended under that announcement, had been finally cancelled.

Pakistani Foreign Minister Qureshi said he did not raise the issue of the funds with Pompeo as he wanted to focus on resetting the atmosphere of the relationship, rather than dwelling on previous decisions.

“Our relationship is not based on transactions, we have to think differently,” he said. “We have to talk not about money, but about principles.”

Qureshi said that if the relationship was to move forward, “it must be based on truth [and] frank, candid conversations”.

“I said this to him, and he agreed, that this blame and shame game does not achieve anything,” he said.

“Yes, we have challenges. On some things, we may think differently, but we have shared objectives as well.”

From the dentist’s office to President House: Dr Arif Alvi becomes Pakistan’s 13th president

PTI’s Dr Arif Alvi was elected the 13th president of Pakistan on Tuesday.

The country’s new president is a politician, dentist and parliamentarian. He has been described as the “chief whip of the PTI” in his profile on the party’s website.

Born in Karachi on July 29, 1949, Dr Alvi acquired a degree in dentistry from de’Montmonrency College of Dentistry, an affiliate of the University of Punjab, and then completed his master’s in prosthodontics (fixing or replacing teeth ) and orthodontics (straightening teeth to improve alignment).

He was the first Pakistani to specialise in orthodontics, according to the PTI’s website.

In 1995, Dr Alvi was certified by the Diplomate American Board of Orthodontists and became the only Pakistani or SAARC dentist to have achieved this level of qualification.

Dr Alvi, who is one of the founding members of the PTI, started his political career as the president of the student union at de’Montmonrency College of Dentistry in Lahore, Pakistan.

He was an active member of the student movements of the Jamaat-e-Islami which occurred during the tenure of General Ayub Khan. Dr Alvi was shot twice during one of the protests on Lahore’s Mall Road at the time. One of the bullets is still embedded in his right arms, which he proudly carries as a mark of his struggle for democracy.

When Imran Khan started the PTI in in 1996, Dr Alvi joined him and began his long career with the PTI.

He contested the 1997 election for the Sindh Assembly PS-89 seat but lost to PML-N candidate Saleem Zia. In the same year, he was appointed the party’s Sindh chapter president.

In 2002 he lost the election on PS-90 to the MMA’s Umar Sadiq. Despite losing, he was made the party’s secretary general in 2006, a post he served on till 2013.

In 2013 he was elected to the National Assembly from NA-250, beating the MQM’s Khushbakht Shujaat. He was appointed the PTI’s Sindh president again in 2016.

During the General Election 2018, he was victorious from Karachi’s NA-247. While campaigning for the elections, he drove a rickshaw in Karachi and garnered attention on social media.

The father of four, who is married to Samina Alvi, is the son of Dr Habibur Rehman Elahi Alvi, the dentist of Jawaharlal Nehru. His father migrated to Pakistan in 1947 and operated a dental clinic in Saddar, Karachi. According to Dr Alvi’s son Awab, his grandfather was a member of the JI and was very close to the party’s then head Syed Munawar Hussain.

Prime Minister Imran Khan nominated Dr Alvi as president on August 18, two days after taking oath as the country’s premier.

Why Imran Khan Must Bat for Civil Society in Pakistan

Prime Minister Imran Khan of Pakistan has set out an ambitious development and reform agenda. He is determined to reign in elite corruption and increase spending on health, education and women’s welfare.

To carry out these important social programs, Mr. Khan needs the support of Pakistan’s battered and bruised civil society. He needs to put an end to the coercion civil society groups have faced from the previous government and the military and help them to function effectively and without constraints.

In the past, Mr. Khan had taken various regressive positions — supporting the discriminatory blasphemy laws, attacking liberals, criticizing the press and describing the Taliban insurgency in Afghanistan as a legitimate jihad against occupying forces — but he has an opportunity to turn the page and embrace a new, more inclusive vision for the country.

Pakistan features on the lower margins of most international human development indexes. It has the worst infant mortality rate. A child born in Iceland has a one-in-1,000 chance of death at birth, while a child born in Pakistan has a one-in-22 chance, according to the United Nations Children’s Fund. Twenty-three million Pakistani children are out of school and millions of children enrolled in public and private schools can barely read or write.

Pakistan needs all the help it can get. Mr. Khan has to find the money and expertise to face these challenges when his government faces immense international debt repayments and collapsing revenues from taxes and exports.

Several international nonprofit groups such as Action Aid, Asia Foundation, Mercy Corps and Open Society Foundation have worked in Pakistan for years.

Civil society organizations have helped during national crises like floods; promoted education in remote, rural areas; and have worked with minority groups such as Christians and Hindus, who are ignored by the state.

Instead of supporting local and international nongovernmental organizations, the Pakistani establishment has responded with a crackdown on these groups. The previous government and the military initiated proceedings to curtail the work and even eject scores of international civil society groups working in Pakistan. Sections of the establishment and right-wing television networks in Pakistan have been promoting allegations linking international NGOs to espionage and antigovernment activities.

Last year, Pakistan ordered 21 international nongovernmental organizations to renew their registration in the country. When they submitted new applications in December, they were denied registration. No official explanation for the decision was provided. They are still waiting for a reply to an appeal.

Various programs run by these groups have been paralyzed for more than a year because of the uncertainty the government has created about their future. And tens of thousands of Pakistanis who work for nongovernmental organizations face the specter of unemployment. Donors such as Western governments are hesitant to come forth.

Pakistani nongovernmental organizations work under extremely difficult conditions, as they don’t have the option of leaving the country nor of effectively challenging clampdowns by the state. Thousands of Pakistani civil society groups, especially the ones working to promote human rights, have been asked to renew their registration and submit answers to highly personal questionnaires. Foreign funding for these organizations has also been suspended.

Mr. Khan cannot make any real progress on his agenda of reform until he ends the curbs on civil society and enlists these groups in creating a better Pakistan.

It is tragic that while Islamabad has pressured and coerced nongovernmental groups, it has opened up greater political and social space for Islamic extremist groups and their affiliates. Pakistan’s Election Commission allowed several extremist groups such as Lashkar-e-Taiba — a State Department-designated terrorist group, which faces sanctions from the United Nations — to contest the recent general elections while using front organizations.

The military has argued that it is mainstreaming these groups by bringing them into the electoral process. But without any de-radicalization program in place, without a commitment from these groups to disarm their tens of thousands of followers and disavow their extremist ideology and show a commitment to democratic processes, allowing them to contest elections only helps them increase their support base.

Extremist groups fielded some 1500 candidates in the elections. While Lashkar-e-Taiba’s proxy failed to win a seat, the Sunni extremist group, Tehreek-i-Labbaik, won two seats in the Sindh Provincial Assembly and got over four million votes.

Mr. Khan needs to rectify this reckless state of affairs as Pakistan remains on the Financial Action Task Force’s “grey list” of countries that have not fulfilled their obligations to curb terrorist activities. According to Western diplomats, the F.A.T.F. review of Pakistan’s compliance in August did not go well.

F.A.T.F. is concerned about extremist groups being allowed to operate as charities in Pakistan while they are listed as terrorist groups by the United Nations. By October, Pakistan could be moved up to the “black list” of F.A.T.F. that includes North Korea and Iran and would result in international sanctions on Pakistan, unless it changes its behavior.

Apart from its direct political consequences, the failure to comply with the F.A.T.F. will also force donor countries to stop bilateral funding, most of which goes to nonprofit groups.

At present there is enormous good will for Mr. Khan, but how long it lasts will depend on whether he will continue policies that are clearly harming Pakistan’s global image, undermining civil society and preventing NGOs from carrying out their tasks.

Policy decisions to return international nongovernmental organizations to their previous status, complying with F.A.T.F. obligations and stopping the growing power of Islamic extremist groups are urgently required. At stake is Pakistan’s democratic future.

Ahmed Rashid is the author, most recently, of “Pakistan on the Brink: The future of Afghanistan, Pakistan and the West.’

PM Khan wants media to give him three months before criticizing his government

Prime Minister Imran Khan has asked that the media give his government three months before criticising its performance, DawnNewsTV reported on Friday.

The statement was made during a meeting with journalists in Islamabad.

The PM promised that three months down the road, there will be a marked difference in the way the country is run. He also mentioned that none of his cabinet members was appointed permanently and could be shuffled around on the basis of performance.

According to Geo.tv, PM Khan, responding to a question, said that while Pakistan cannot fight the US and looks to improve ties with Washington, the government will not give in to any unjust demands made by the White House.

He mentioned that Pakistan seeks peaceful relations with India, Afghanistan and Iran as well.

According to DawnNewsTV, PM Khan also told journalists that he has directed the chairman of the National Accountability Bureau to continue an indiscriminate accountability process in the country.

He added that if any member of the government is suspected of any indiscretion, they should also be held accountable.

The prime minister also pointed out that Pakistan’s circular debts stands at Rs1.2 trillion and that progress would not be possible without across-the-board accountability.

During the meeting, PM Khan was also asked about his usage of a helicopter for travel to and from Banigala, which he defended as a way of saving citizens from the trouble of traffic holdups.

Imran Khan gives 2-week deadline to recover stashed money

Islamabad, Pakistan: Fulfilling his poll promise to clampdown on corruption, Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan on Tuesday gave a deadline of two weeks to a task force to chalk out a plan to recover unlawfully acquired foreign assets and stashed wealth.

On Monday, the task force chaired its first meeting, where various government departments informed the unit of the current status of pending probes of money laundering and financial fraud cases, officials were quoted by The Express Tribune, as saying.

Khan has said that his topmost priority is to retrieve hidden offshore assets and promised to bring back ill-gotten wealth in overseas banks.

According to the terms of reference (ToR) of the task force, Khan has set a deadline of two weeks for the body to take steps for the “expedient return of unlawfully acquired assets from abroad”.

Meanwhile, the chairman of the task force has directed Pakistan’s Finance Ministry to share earlier reports prepared by the committees set up under the purview of the country’s Supreme Court to recover the unlawfully acquired foreign assets.

The task force has been asked to review all cases of financial fraud pending before the government departments and organisations. The body will also be responsible for the investigation of the existing mechanism, international agreements, working out modalities to fast-track the recovery of ill-gotten wealth and undeclared offshore assets, and ensuring coordination of the Pakistan government with other governments on the same, The Express Tribune report said.

Recently, Pakistan gave its citizens the last opportunity to declare their wealth and offered them offshore and domestic tax amnesty schemes. While over 5,000 people availed the offshore scheme and declared over USD 8 billion assets, the repatriation to the country was less than USD 70 million.

On August 19, in his first address to the nation after being sworn-in as Pakistan’s prime minister, Khan vowed to tackle corruption and said that he would form a task force to bring back swindled money to the country. (ANI)

The end of discretionary funds: rhetoric and reality

ISLAMABAD: In its meeting on Monday evening, the federal cabinet decided to abolish the discretionary funds of the prime minister, federal ministers and development funds for MNAs, a decision which has been widely projected as an unprecedented step by the Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (PTI) government. The reality is quite the opposite.

Very few observers have cared to check whether these funds existed before. A sum of just Rs80 million a year used to be allocated to the prime minister, which he would largely spend on entertaining the applications of needy people for free medical treatment and the like. Even incumbent government officials agree this was not a substantial allocation.

A special fund of Rs1 million used to be allocated to each cabinet member, but had already been abolished by the previous government. The practice of releasing secret funds to different ministries had also been stopped by the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) administration; the intelligence agencies remained the only exception to this rule.

The PML-N government had also announced the abolition of discretionary development funds to MNAs, although this practice continued under different official nomenclature.

So what is different? The hefty allocations made for development projects in the constituencies of ruling coalition MNAs is the key point. Abolishing this would really be a big test for the government. These funds are what the PTI government has decided to stop, terming them as “discretionary funds”. Ideally, development is the domain of the local government apparatus, not that of federal lawmakers, since financial resources were largely devolved to the provinces under the 18th amendment to the constitution.

The abolition of these funds was promised in the PTI manifesto published in 2013. The party had announced an end to this practice in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa when it formed the government there five years ago. Did it keep the promise? The answer is negative.

Before pinning so much hope on such pledges, it is important to ascertain the fate of such measures announced in the past so as to spell out the challenges faced in translating rhetoric into reality. In the early days of the Nawaz Sharif government in 2013, there was a similar air of optimism. Austerity was the buzzword, as with the newly ensconced PTI government.

The first budget of the PML-N government unveiled a 45 per cent cut in the expenses of PM House, reducing it from Rs725 million a year to Rs396 million. However, they started increasing again from Sharif’s second year in office onward. By the time the PML-N government presented its last budget in May, some Rs986 million was budgeted for PM House, significantly more than the slashed budget announced in 2013.

Likewise, non-development expenditures were trimmed by 30 per cent in line as part of the austerity drive at the time. This resulted in the slowing down of office work, as staff would complain of shortages of paper, ink and other supplies, and about restrictions on the use of telephones. Ultimately, the government had to backtrack on its decision to cut financial corners.

Similarly, a radical decision was taken by the erstwhile PML-N government to abolish development funds for MNAs. This was made controversial by the unconstrained abuse of the funds by former Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) premier Raja Pervez Ashraf. He lavished funds totaling Rs47 billion on his native Gujar Khan, while a further Rs5 billion was granted to other influential PPP lawmakers and their allies.

When the matter was taken up by the Supreme Court, it directed action against Pervez and ruled that the allocation of discretionary funds to the prime minister and chief ministers for development projects was an unconstitutional practice.

“The government is bound to establish procedure/criteria for governing allocation of such funds for this purpose,” the Supreme Court noted in its verdict on December 5, 2013.

When the PML-N formed the government, it initially refused to grant funds to MNAs for handpicked development schemes in their constituencies. Meanwhile, any announcement by the prime minister for, say, the construction of a road or the provision of piped natural gas, was routed through the Planning Division. The Nawaz Sharif government faced raucous opposition when it approved funds for the Rawalpindi-Islamabad metro bus project, with critics dubbing it a violation of the Supreme Court order in the Raja Pervez Ashraf case, although the plan was expedited via the Planning Division, not from any discretionary fund.

In an apparent attempt to counter-balance this criticism, Nawaz announced the establishment of 46 state-of-the-art hospitals across the country, a move which failed to make any headway due to the poor conception of the project. It gave rise to questions as to whether administrative charge and financing of the hospitals would be undertaken by provincial administrations or the federal government.

However, the government found itself under real pressure from MNAs to restore the funds after the destabilising crises created by the PTI-led dharna in 2014 and the Dawn leaks controversy in 2016. It was torn between obeying the court’s order banning the discretionary allocation of development funds and appeasing lawmakers in the run-up to the 2018 general election.

It sought and found an innovative way of releasing the controversial grants. They were allocated under the heading of the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals, which require the government to invest in the provision of clean drinking water, energy and poverty alleviation – all through the Planning Division and mostly to treasury MNAs, with the major chunk allocated to politicians from Punjab.

The PTI provincial government in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa behaved no differently, violating its 2013 manifesto pledge and the Supreme Court’s order. In 2014, PTI Chairman Imran Khan wrote a letter to the then chief minister, Pervez Khattak, directing him to stop the release for discretionary funds for himself, cabinet members and MPAs. What happened in reality is a matter of public record.

The following year (2015), Rs8.5 billion was released to MPAs. Whereas the PML-N government had made such allocations under the UN Sustainable Development Goals, the KP government did so under its Annual Development Programme, doling out funds in the form of special packages and district development initiatives. A significant chunk went to the constituencies of treasury lawmakers and ministers, according to according to Centre for Governance and Public Accountability (CGPA), which obtained the data courtesy of Right To Information (RTI) laws.

Another RTI request by the CGPA brought to the public’s attention the fact that Khattak and his finance minister, Muzaffar Said, collectively spent Rs837 million in the financial year 2017-18 alone, sourcing it from the discretionary funds for local governments at their disposal.

Some Rs557 million was allocated to Khattak and Rs280 million to Said, according to the data obtained by the CGPA. The single highest allocation of Rs490 million was made for projects in Khattak’s home district of Nowshera, followed by Rs200 million to Said’s home district of Lower Dir.

Advertisement

Populism and Governance

IMRAN Khan has set ambitious goals for his government. While his priorities seem right the challenges are enormous. His first address to the nation has indeed inspired people giving them some hope.

No Pakistani leader in the recent past has spoken so earnestly about the problems faced by the common people and also the difficulties confronting the nation. He believes he can change the destiny of this crisis-torn country. All that sounds reassuring. But can he deliver on his promise?

The transition from the position of an opposition leader to one of power is never easy, particularly when it has taken one decades of relentless struggle to reach that level. Khan’s outburst during his first speech at the National Assembly following his election as prime minister was seen to prove the point.

He lost his cool in the face of the PML-N’s unruly protest and went into his confrontationist ‘container’ mode. He, however, appeared more in control during his televised address.

Notwithstanding some populist rhetoric, the prime minister has given his vision of turning Pakistan into a social welfare state. His emphasis on human development is in contrast with the PML-N government’s obsession with big-ticket infrastructure projects. Health, education, environment and institutional reform are at the top rung of Khan’s priorities.

The PTI government has taken populist rhetoric too far on the issue of accountability.

It is rare for our political leaders to take such an emphatic position on critical issues directly linked to the well-being of the masses.

The lack of investment on human infrastructure has been a major cause of Pakistan lagging behind in economic and social development. Surely successive governments had pledged to improve education and health services but there has never been any serious effort to fulfil those promises.

Financial constraints have also been a factor in low investment in the social sector. Khan’s promise to get millions of children into school needs massive resources. It is a similar story in the health sector. The party may have succeeded to some extent in reforming the education and health sectors in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa that it ruled for five years, but a lot more needs to be done.

The financial crisis is certainly the most serious concern for the new government as acknowledged by the prime minister. The current account deficit and falling foreign exchange reserves need urgent action. But Khan does not seem to have clear thoughts on the question of whether to seek an IMF bailout or to see if other options are available to deal with the crisis. The massive debt burden has limited our options. The delay in making decisions could worsen our predicament.

Equally serious are the burgeoning circular debt affecting the power sector and the massive losses incurred by public-sector organisations that have added to our financial woes. There is an urgent need to formulate a clear policy to stop this haemorrhaging. The government has made it clear that it did not have any plan to privatise the losing state-owned enterprises. But it will be hard to revamp organisations like PIA and Pakistan Steel Mills and make them run more efficiently by just making changes at the top. The government will have to take some tough and unpopular measures early in its tenure. It remains to be seen whether it is ready to bite the bullet while keeping its populist promises.

Khan has promised to double the tax revenue by reforming the FBR and appealing to the conscience of the people to pay taxes. That sounds great. But it requires much more to instil the tax culture in society. There is a lot of symbolism involved in Khan’s austerity drive. His decision not to live in Prime Minister House and cut down on protocol certainly has great symbolic value, but the administration needs to do much more in order to decrease public expenditure.

Given the enormous challenges of governance, the new government needs a more prudent approach on the political front. But there seems to be no let-up in the party’s confrontational politics. The decision to put the former prime minister and his daughter on the Exit Control List does not make any sense as they are already in prison. The move smacks of vendetta and it only serves to divert attention from the government’s reform agenda.

Also on the issue of accountability, the PTI government has taken populist rhetoric too far. Indeed, there is a need for across-the-board accountability but the government’s actions reinforce allegations of a witch hunt. The pledge of bringing back looted money is nothing more than rhetoric. It would be much better for the PTI administration to let the law take its course rather than have its leaders trumpeting the mantra day and night.

Although Khan has vowed to implement the National Action Plan, there seems little clarity on how the administration plans to deal with the menace of religious extremism that threatens to tear apart our social fabric. There was not even a mention of the problem of violent extremism in the prime minister’s address to the nation.

In order to accomplish the ambitious target, the prime minister needs a good team. Surely the 22-member cabinet has many capable and experienced people, but there is no new blood to bring in dynamism and fresh thinking in the administration. One can understand the compromises one has to make in a coalition setup, yet some space could have been created to bring in new faces.

Most shocking has been the choice of chief minister of Punjab. The logic offered by Khan on the odd appointment that Sardar Usman Buzdar comes from the most backward region is astonishing. The selection of a man who had never held any public office before and has a dubious personal record to head the government in the country’s biggest province is more alarming as the provinces are responsible for carrying out the reform agenda announced by the prime minister.

Notwithstanding Imran Khan’s commitment of building a ‘naya Pakistan’, there is now a need for the new incumbent to focus more seriously on governance rather than pandering to populism. Governance is serious business and must be taken as such.

The writer is an author and journalist.

PTI government lifts political censorship on PTV, Radio Pakistan

Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) government on Tuesday lifted political censorship on the state-run Pakistan Television (PTV) and Radio Pakistan by allowing these to air point of views and news of all political parties without any discrimination.

Federal Minister for Information, Broadcasting and National Heritage Fawad Chaudhary spoke out via Twitter saying that, “As per vision of [Prime Minister] Imran Khan ended political censorship on PTV, clear instructions issued for a complete editorial independence on PTV and Radio Pakistan, drastic changes will be visible in information department in coming three months”.

Chaudhry elaborated that PTV and Pakistan Cricket Board (PCB) would not be used as a private property by any government anymore rather these would be used to portray and promote the country’s positive image.

Before taking the reins of the ministry, the PTI leader said that the official media of the country which includes Associated Press of Pakistan (APP), PTV and Radio Pakistan would be improved and made independent with no political interference drawing parallels to foreign media outlets.

He doubled down on depoliticising the national news broadcaster and expressed making it independent like the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC).

During the Pakistan Muslim League –Nawaz (PML-N) government’s tenure, opposition parties called for PTV to run news and views of the opposition parties, but to no avail.

In view of the PML-N government’s response, the opposition parties had labelled the national broadcaster as the supposed ‘mouth piece’ of the government.

Moreover, opposition parties claimed that the political decisions and unnecessary coverage in support of the then government was a catalyst for PTV being mired by financial problems.

Outgoing setup suggests harsh economic measures to PTI

In the wake of the blow back by the opposition, the former PML-N government rolled out PTV Parliament, a new channel.

The new channel aimed to provide coverage of the parliamentary proceedings, as well as, being a platform through which citizens could delve into their elected representatives’ performance.

The former government launched this new channel despite knowing that PTV was already facing financial crunch.

Therefore considering the financial crunch PTV is currently facing, Hussain directed PTV and PBC to make all out efforts to generate revenues by improving their content, programming and screen.

He had also directed PTV Sports to focus more on promoting other traditional games of the country such as Kabaddi, Volleyball along with Cricket and the national game Hockey.

Parched for a Price: Karachi’s Water Crisis

KARACHI, Pakistan – Orangi is a maze, a spider’s web of narrow, winding lanes, broken roads and endless rows of small concrete houses. More than two million people are crammed into what is one of the world’s largest unplanned settlements here in western Karachi, Pakistan’s largest city.

But Orangi has a problem: it has run out of water.

“What water?” asks Rabia Begum, 60, when told the reason for Al Jazeera’s visit to her neighbourhood earlier this year. “We don’t get any water here.”

“We yearn for clean water to drink, that somehow Allah will give us clean water.”

It is so rare for water to flow through the taps here that residents say they have given up expecting it. The last time it flowed through the main pipeline in Begum’s neighbourhood, for example, was 33 days ago.

Instead, they are forced to obtain most of their water through drilled motor-operated wells (known as ‘bores’). Ground water in the coastal city, however, tends to be salty, and unfit for human consumption.

“When we shower, our hair [becomes] sticky [with the salt], our heads feel heavy,” says Begum.

The only other option for residents is to buy unfiltered water from private water tanker operators, who fill up at a network of legal and illegal water hydrants across the city. A 1,000-gallon water tanker normally costs between $12 and $18. Begum says she has to order at least four tankers a month to meet the basic needs of her household of 10 people.

Farzana Bibi, 40, says she has to ration out when she showers and washes her family’s clothes, because she can not afford to buy enough water every month.

But not everyone in this working class neighbourhood can afford to buy water from the tankers or to pay the approximately $800 its costs to install a drilled well for non-drinking water.

“I’m piling up the dirty clothes, that’s how I save money,” says Farzana Bibi, 40, who manages a household of five people on an income of roughly $190 a month. “We bathe two days in a week.”

Asked how she gets by, with so little water coming via the taps and no access to a saltwater source to clean dishes or laundry, she seems resigned.

“I lessen my use. Sometimes I’ll take my clothes to my cousin’s house or my sister’s house to wash them. Sometimes I’ll get drinking water from them. One has to make do somehow.”

When she washes her clothes, she says, she makes sure not to leave the tap on. She’ll fill a basin with water and wash her dishes in that, rather than under running water. She waits until there is at least a fortnight’s worth of dirty clothes before beginning to wash them. Every drop of water, she says, needs to be accounted for.

But despite all this rationing, the water tank at her home is almost dry.

“There is a small amount of water,” she says. “I am saving it to drink. When I have money in my hands, I’ll get a tanker.”

Orangi’s problems, while acute, are not unique in Pakistan’s largest city. Karachi’s roughly 20 million residents regularly face water shortages, with working class neighbourhoods the worst hit by a failing distribution and supply system.

Areas such as Orangi, Baldia and Gadap, some of the most densely populated in the city, receive less than 40 percent of the water allotted to them, according to data collected by the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP), an NGO that works on civic infrastructure and citizens’ rights in the area.

On average, residents in these areas use about 67.76 litres of water per day, according to data collected by Al Jazeera. That includes the water they use for drinking, cooking, cleaning, washing clothes, bathing and sanitary uses.

So what is going on here? How is it possible that in one of the largest cities in the world, there simply isn’t enough water being supplied? Is it because the reservoirs and water sources supplying Karachi just aren’t large enough for this rapidly expanding megacity?

The answer to these questions is somewhat surprising.

Karachi draws its water mainly from the Keenjhar Lake, a man-made reservoir about 150km from the city, which, in turn, gets the water from what’s left of the Indus River after it completes its winding 3,200km journey through Pakistan.

Through a network of canals and conduits, 550 million gallons of water a day (MGD) is fed into the city’s main pumping station at Dhabeji.

That 550MGD, however, never reaches those who need it. Of that water, a staggering 42 percent – or 235 MGD – is either lost or stolen before it ever reaches consumers, according to the Karachi Water and Sewerage Board (KWSB), the city’s water utility.

Karachi’s daily demand for water should be about 1,100 MGD, based on UN standards for water consumption for the megacity of more than 20 million. If that estimate – considered generous by local analysts – were to be pared down, however, Karachi’s current water supply should still be adequate to service most of the city’s needs.

“If 550GMD of water actually reaches Karachi, then right now, with conditions as they are, we would be able to manage the situation very well and provide water to everyone,” says Ovais Malik, KWSB’s chief engineer, who has been working for the utility for more than 12 years.

So where is it all going?

Malik complains that the water supply infrastructure in the city is aged, parts of it running for more than 40 years, and that the funds simply are not there to fix the problems.

KWSB is, by any standard, a sick institution. This fiscal year, it estimates that it will be running at a deficit of 59.3 percent. Only about 60 percent of consumers pay their bills, with the biggest defaulters being government institutions themselves, which owe KWSB about $6 million in arrears.

Moreover, Karachi has expanded in a largely unplanned fashion over the last several decades, with informal settlements ‘regularised’, but not properly brought under the ambit of civic services, he says.

“Our [settled] area has grown too much. Our…system has not been able to bear it,” says Malik.

Farhan Anwar, an architect and urban planner, told Al Jazeera that KWSB was almost bankrupt.

“There is nothing left for any kind of maintenance or capital investment.”

That lack of capital investment affects not just the ability to provide water, but to make sure that it is clean enough to be consumed, Anwar argues.

“The water is obviously contaminated,” he says. “There are discharges, there are cross-connections of water, where sewage lines are leaking into supply lines. Construction practices are such that…often sewage lines are side by side with water lines, or even above them.”

And KWSB never seems able to get around to addressing these problems, several analysts said.

“There is corruption, inefficiency, political interference, so it’s an organisation rooted in a number of problems.… You need institutional reform, to begin with. Instead of starting by fixing the pipes, you need to fix the institution that fixes the pipes,” says Anwar.

The problem, however, is not just leakages and inefficiency in the system: it is theft.

The bulk of Karachi’s ‘lost’ water is being stolen and sold right back to the people it was meant for in the first place.

WHO IS STEALING KARACHI’S WATER?

Akhtari Begum, 48, has to manage a household of five people on her husband’s income of $160 a month.

She ends up spending more than a third of that on water.

“Water does come [in the main line], but it gets stolen before it gets to us,” she says. “So we don’t get any water, we have to get tankers.”

A typical 1,000-gallon water tanker costs anywhere between $12 and $16, depending on where you are in the city, what time of year it is, and how desperate you might be.

Water tankers have been a part of Karachi’s water supply landscape for decades. Initially introduced as a stop-gap measure while the KWSB was meant to be expanding the city’s water supply infrastructure, they have grown to dominate the sector.

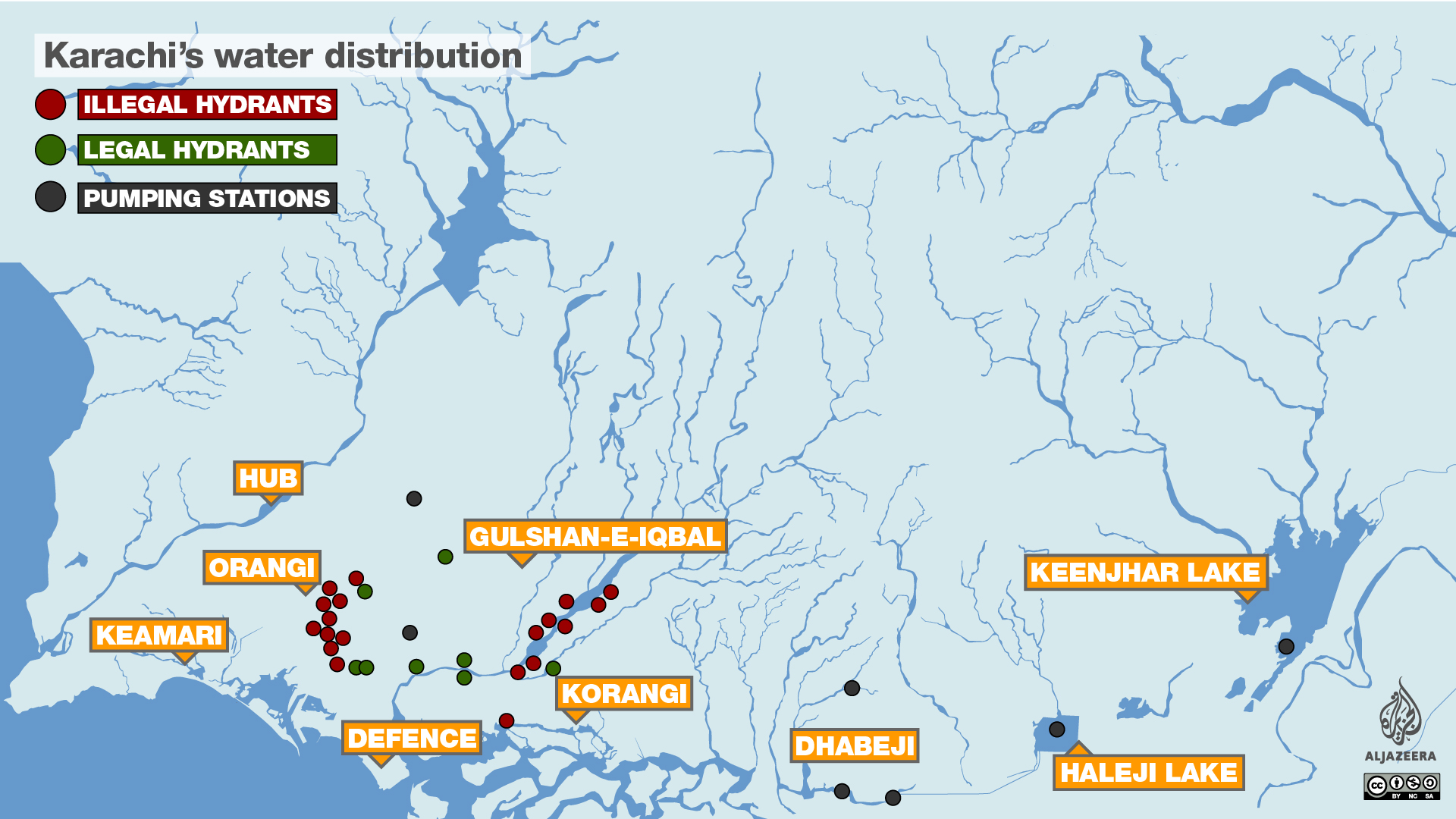

Today, there are more than 10,000 tankers operating across the city, completing roughly 50,000 trips a day, according to Noman Ahmed, the head of the architecture and urban planning department at Karachi’s NED University. They are meant to fill up at 10 KWSB-operated hydrants, but the business is so lucrative that more than 100 illegal hydrants operate across the city, tapping into the city’s mains to steal water.

“There are more than a hundred of them [illegal hydrants], and those are just the ones that have been identified. Every day there’s a new one being made somewhere,” says Anwar Rashid, a director at the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP), which tracks the tankers’ illegal activity.

“They’re visible easily. They tap into the bulk mainline. They syphon off the water. And then there are tankers standing there, and they’ll fill up directly from the [illegal hydrant] and then drive off.

“When they take from the bulk, then that means that the water that was meant for residential areas will be reduced,” says Rashid.

The scale of the theft is staggering.

If tankers in Karachi are making 50,000 trips a day, with each trip priced at an average price of Rs3,000 (prices vary between Rs1,200 to Rs7,000), that amounts to an industry that is generating Rs150,000,000 a day.

That’s $1.43 million, every day. In a month, that adds up to $42.3 million. By the end of the year, stealing water in Karachi is an industry worth more than half a billion dollar.”

THE MAFIA IS VERY STRONG”

“We have carried out more than 400 operations against illegal hydrants in recent years,” Rizwan Hyder, a spokesperson for the KWSB, told Al Jazeera. “We are acting against these things … and working with the police …. We have lodged scores of cases against people operating illegal hydrants.

The local police station chief in the area where [there is] a hydrant is the one who is responsible for acting against them. The moment they inform us, we act against it. In the last few days, we have taken action against three illegal hydrants in Manghopir [near Orangi Town].”

But the people who are meant to be controlling the theft are the ones cashing in, tanker operators, analysts and former KWSB employees told Al Jazeera.

“Unauthorised hydrants are run with the connivance of the water board and the police,” claims Hazoor Ahmed Khan, the head of one of the city’s main water tanker unions. “There are about 100 illegal hydrants still operating in the city…most of them are in Manghopir, in Baldia, in Malir, in Landhi, and Korangi. They’re running in Ayub Goth on the Super Highway.”

“[Illegal hydrants] can only be run by people who are in the government, or in the Karachi Water and Sewerage Board, the police, or the revenue department,” claims the OPP’s Rashid. “And they all have the share in it.

His view is borne out by a former KWSB chief, who spoke to Al Jazeera on condition of anonymity, given the sensitivity of the subject.

“The mafia is very strong …. There is no doubt that the illegal connections that are made, our KWSB man knows about it. Even if it is an [illegal] connection within a building, he will know that a connection has been installed in the night,” he says.

“The valve man takes his money, the assistant engineer takes his money … I could never say that there is no corruption in the KWSB. But I also know that the builder has so much influence, that no matter who [the KWSB chief] is … he will get a call from [a] minister [or senior bureaucrat] to just do it.”

The ex-chief said he had himself received phone calls of this nature. Another current senior KWSB official who asked to remain anonymous confirmed that he, too, had received such phone calls from members of the government, asking him to curb operations against illegal hydrants.

The result is a system where water is being stolen, commodified and then sold to citizens through the free market. A market, analysts say, that inherently favours the rich over the poor.

“The social contract, regarding what is the role of the state vis-a-vis the people, that is now mediated through the medium of money and privatisation,” says Daanish Mustafa, a professor of geography at Kings College London who studies the sector. “The rights-based approach to water, that water is a fundamental right of the people and a fundamental responsibility of the state, that has ended.

“Who is going to make money getting water to a poor man? Where there is money, the water will reach very quickly, and very easily.”

When asked about KWSB personnel being involved in the theft of water, the KWSB’s Hyder told Al Jazeera, “It has never been our position that no member of our organisation is involved [in the theft of water]. But the moment someone is found [to be] involved in this, they are fired and charged under the law. We have charged our own staff … we have zero tolerance for this.”

There are periodic drives to shut down these illegal operations. But none last for long.

“If there is ever a crackdown, if there is pressure, they do not cut the [hydrants] on the bulk mains, they just demolish a little bit of the infrastructure [of theft], and then four days later it’s back up and running,” says Rashid.

“The illegal hydrants are still running. They can never be shut,” says the former KWSB chief.

If the very people responsible for shutting down the illegal theft of water are the ones benefitting from it, who will watch the watchmen?

“If I fix the water system in an area, then no one will take a tanker. If we fix the system, whatever illegality is happening will [be] finished,” says the current senior KWSB official.

“These things are possible. We can do them,” he adds. “But we don’t want to do them.”

CAN’T AFFORD IT, CAN’T LIVE WITHOUT IT

For 16 years, Ali Asghar, 75, tended to his small herd of cows and buffalo on a small plot of land behind his cramped four-room house in Orangi. Four years ago, when the water supply to his area began to suffer, he had to give them up.

Today, his entire household of 17 people is dependent on water bought from tankers.

The biggest injustice, he says, is that he is still paying his bills to KWSB, for water that never comes.

“The [mains] pipe is lying out there, completely dry,” he says. “This is how it is in this whole neighbourhood.”

“The people of the water board are the ones who are doing this. They are the ones who create the water crisis, and they’re the ones who don’t provide the water, and take the bills,” he says, his voice rising in exasperation. “For every job, there is a price. And if you don’t have money, you won’t get anything done.”

Ali Asghar, 75, says he still has to pay bills to the utility company for water that never comes in the pipes

A few streets away in Orangi’s spider web, Rabia Begum says the city’s poor are trapped because no matter what the price, people need water.

“We cannot tolerate the expense of water … and we cannot live without it,” she says.

In March 2013, four gunmen on motorcycles boxed in a car near the Qasba Mor intersection in Orangi. They proceeded to spray the car with bullets, killing its occupant, Perween Rehman.

Rehman was the director of OPP, and had worked tirelessly for the rights of Karachi’s working class communities, particularly when it came to land titles and access to water. Much of her research focused on documenting the locations of illegal water hydrants, for which she received several death threats.

Shortly before her murder, Rehman spoke to a documentary crew, who were making a film about her work. Her words ring as true today, four years later.

“It is not the poor who steal the water. It is stolen by a group of people who have the full support of the government agencies, the local councillors, mayors and the police; all are involved.”

Who will watch the watchmen, while the poor remain parched – for a price?