What makes Muslim parents murder their own children, especially daughters, is a question that has leapt to the front pages of newspapers all across Canada. It is, unfortunately, not the first time that Muslim parents in Canada have murdered a female child. Such murders are known as ‘honour killings’ where parents murder their daughter/s to “protect the family honour.”

It was only in December 2007 when a Pakistani father (along with his son) murdered his 16-year old daughter, Aqsa Parvez, in a suburb of Toronto. Her crime: she wanted to act and dress like other teenage girls in her school. Fewer than two years after Aqsa’s murder, another Muslim father in Canada murders not one but three daughters.

On the morning of June 30, 2009, a car was found submerged in the Rideau Canal in Kingston, Ontario, a small university town some 250 km East of Toronto. Found dead in the car were the three Shafia sisters: Zainab, 19, Sahar, 17, and Geeti, 13. Also found dead in the car was 50-year old Rona Amir Mohammad, who was the girls’ stepmother. Weeks later the Canadian police arrested the girls’ parents Mohammad Shafia, 59, and Tooba Mohammad Yaha, their 39-year old mother. The police also arrested the girls’ brother Hamed Shafia, 18, and accused the three of murdering the three teenage girls and their stepmother, Shafia’s first wife who did not bear any children.

A little over two years later, the accused are now standing trial in Kingston. As the trial proceeds, gruesome details emerge about the family that conspired to kill its own daughters. Once again, it is a familiar story where a father is unhappy with his teenage daughters and decides to kill them “to protect his family honour.”

Shafias, originally from Afghanistan, moved to Canada in 2007 and settled in a suburb of Montreal. The court proceedings reveal an overbearing father who was not happy with the way his daughters were growing up in Canada. He was particularly concerned about his eldest daughter, Zainab, who fancied a Pakistani young man of modest means. Mohammad Shafia did not approve of the relationship.

Over the next two years an acrimonious relationship develops between the father and the eldest daughter. Shafia was spying on the daughters and was aware of the digital photographs of his older daughters with their friends. He was not pleased.

While Shafia was away in Dubai for work, Zainab wedded the Pakistani young man in a small ceremony attended by her immediate family members. Missing from the ceremony was Shafia and the groom’s entire family, who also did not approve of the union.

What transpired later in the day after the Nikkah ceremony revealed that Zainab in fact got married to spite her father. According to the Toronto Star, she told her uncle: “… this boy doesn’t have money and he’s not handsome. The only reason I’m marrying him is to get my revenge. I will sacrifice myself for my other sisters. At least they will get their freedom after me.’’ Zainab told her mother after the Nikkah that she would be willing to dissolve the day-old marriage to please her mother. Soon the family was off to a vacation in Niagara Falls. On their way back from vacation they made an overnight stop in Kingston. Next morning, four dead bodies were found trapped in the submerged car.

The police suspected the family from the very beginning. The evidence found around the crime scene suggested that the submerged car was pushed into the water by another car, which also belonged to the family. Further investigations revealed that the four women were dead before the car went into water, suggesting that it was not a freak traffic accident, as was initially claimed by the parents.

The police planted surveillance equipment in the Shafias’ home and car, and also bugged their phone. The taped conversations played in the courtroom revealed a calculated plot by Mohammad Shafia to kill his daughters. They painted a picture of a man who had no remorse for killing his own flesh and blood. Geeti, who was 13, and his first wife, Rona were the collateral damage. Still Shafia is heard on tape saying: “I am happy and my conscience is clear,” and that his daughters “haven’t done good and God punished them.”

Was it really a punishment from God or from a sadist father who killed in cold blood because his daughters disobeyed him? He called his daughters “filthy and rotten children” and expressed his resolve to do the same 100-times over.

While the tapes reveal a merciless man who was a captive of his tribal norms, which he brought with him from Afghanistan, a swoop of Hamed Shafia’s computer by the police also revealed a cunning man who was searching the Internet to plot murders. Other searches conducted on the laptop computer focused on what would happen to one’s business and property if one was incarcerated.

Many in the West associate ‘honour killings’ with Muslim societies. However, the deplorable practice can be found in several non-Muslim majority societies. In India, for instance, the practice is more frequent in rural settings where village councils at times have sanctioned murdering the couple who had eloped or married without the family’s consent. Earlier this week a judge in Uttar Pradesh sentenced eight men to death and 20 others for life imprisonment for honour killings committed in 1991. In May 2011, the Indian Supreme Court had already recommended capital punishment for those convicted of honour killings, thus enabling the lower courts to award stricter punishments.

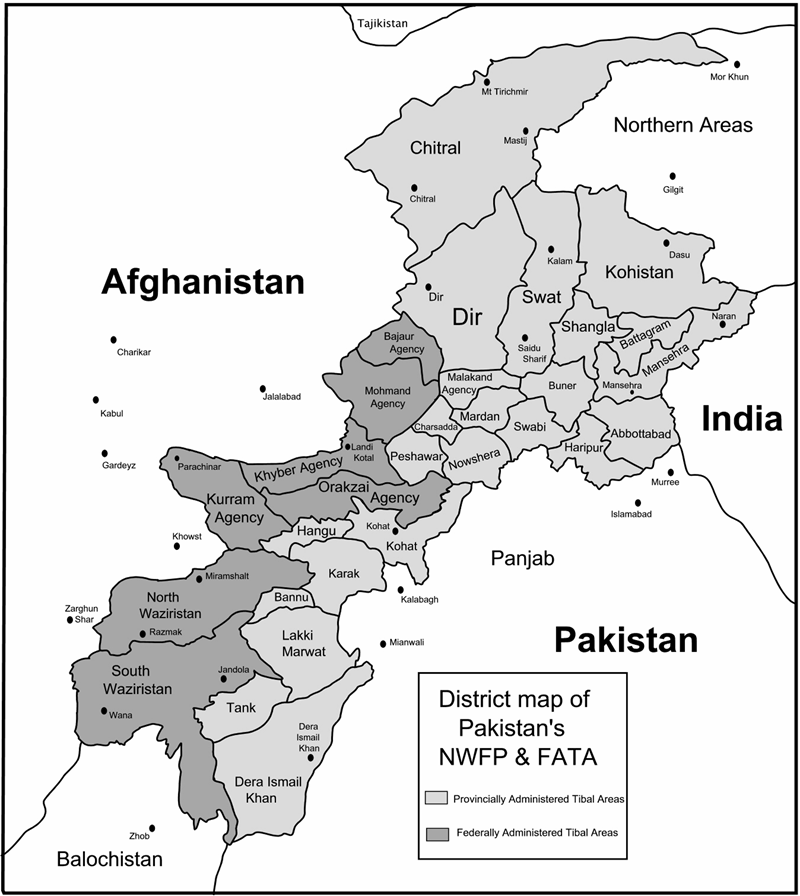

In Pakistan and several other Muslim countries, female victims of honour killings seldom get justice. While laws against honour killing have been on the books in Pakistan since 2005, however the conviction rate has been despicably low. In Khyber Pukhtunkhwa (KP), a mere 8 per cent of those accused of honour killings were convicted in 2009. *Of the 33 women and 18 men murdered in honour killings in 2009 in KP, 83 per cent of the accused were husbands, fathers, brothers and other male relatives of the deceased.

Research from Pakistan, Jordon, and other countries revealed that often mothers of murdered women approach the sharia courts as their legal heirs and sought and received pardon for the accused father, brother or other male relative of the murdered girl in a Diyat (blood money) arrangement.

The Shafias will have to face justice. Mohammad Shafia’s wealth and property cannot buy him freedom in Canada. He murdered his daughters. It was not an act of passion, but a premeditated one. Shafia thinks he acted honourably.

However, nothing is more dishonourable and cowardly than murdering children.

*Sajid, Imran A.; Khan, Naushad A.; Farid, Sumera. Violence Against Women in Pakistan: Constraints in Data Collection. Pakistan Journal of Criminology. Volume 2, No. 2, April 2010, pp. 93 – 110.

Murtaza Haider, Ph.D. is the Associate Dean of research and graduate programs at the Ted Rogers School of Management at Ryerson University in Toronto.